|

管理员

|

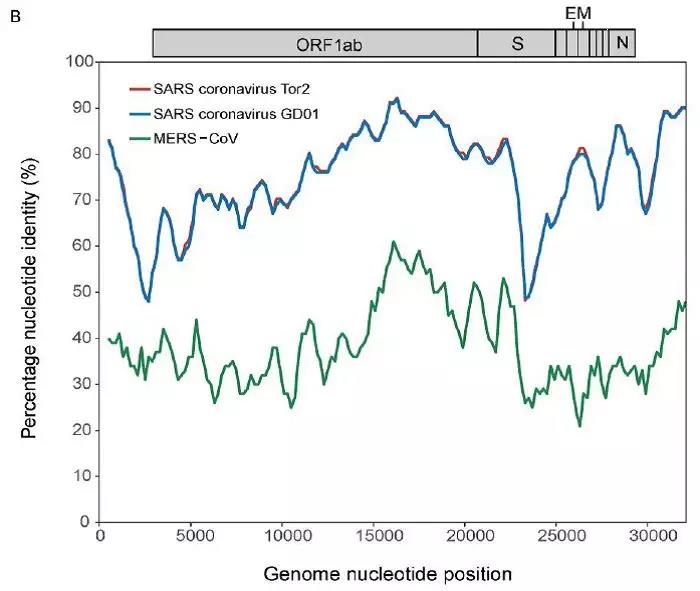

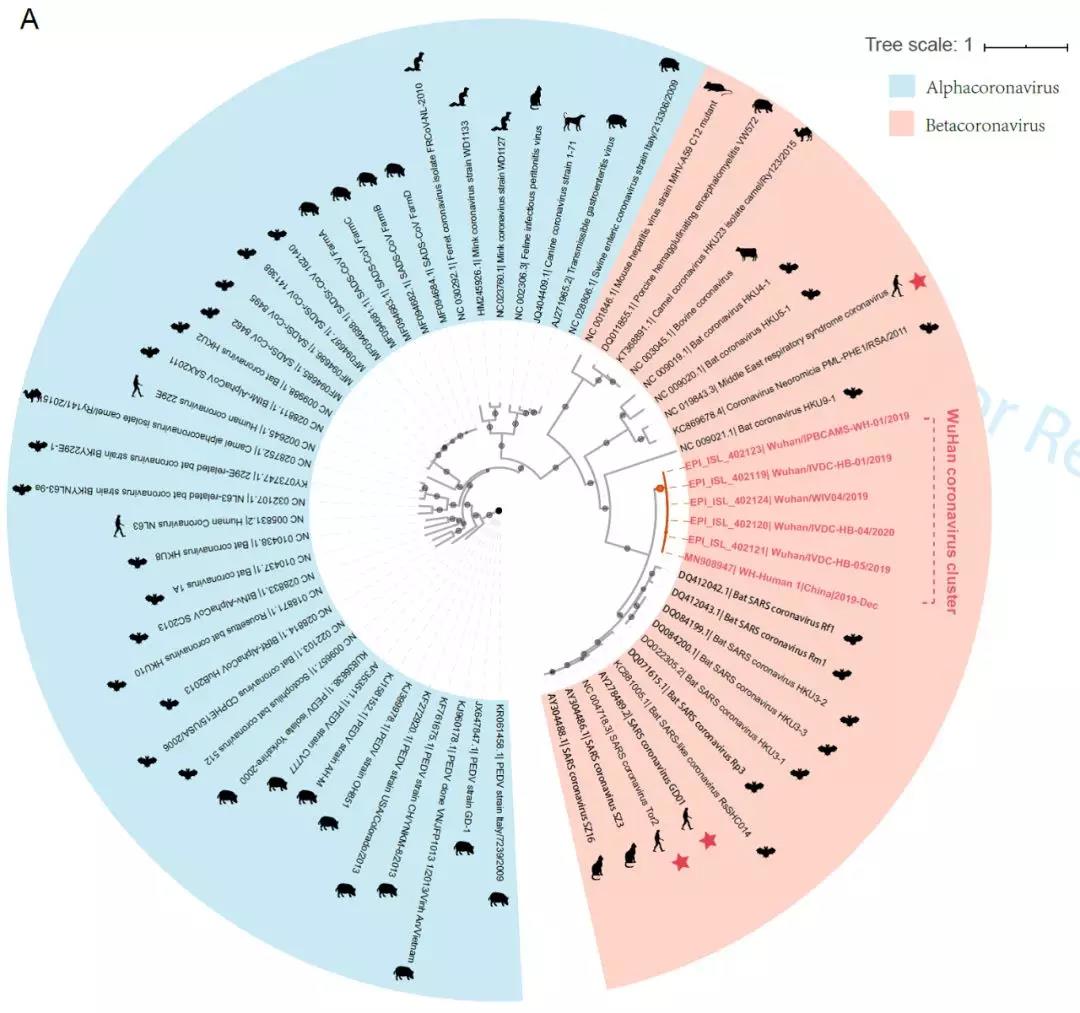

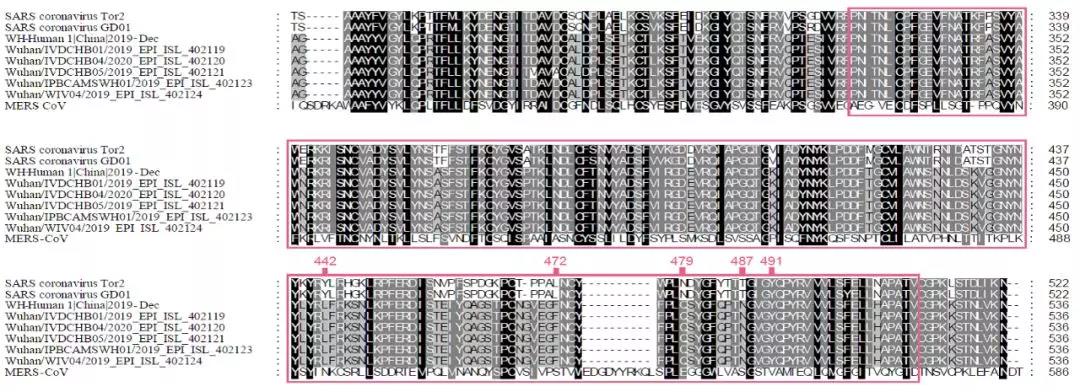

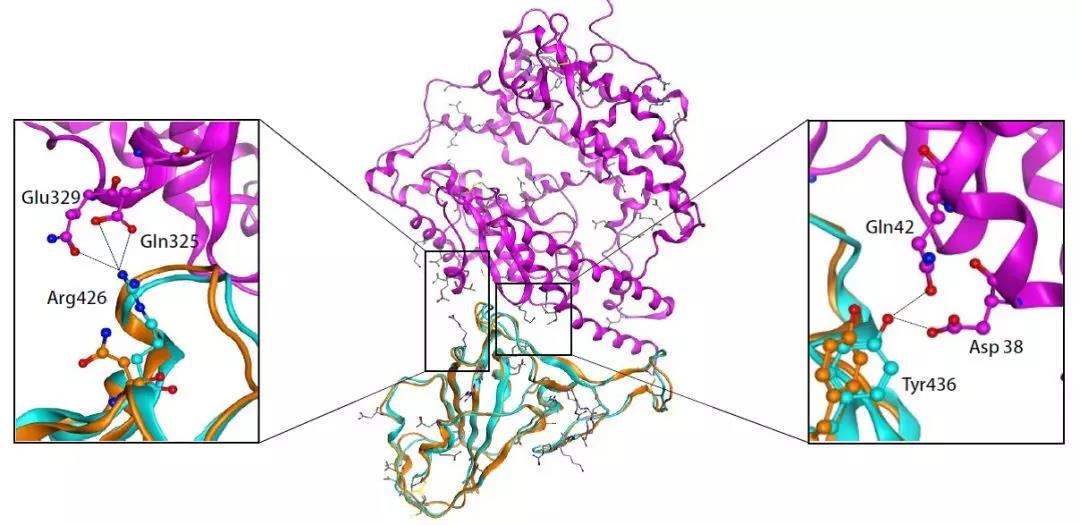

“新型冠状病毒(2019-nCoV)溯源、致病及防治的基础研究”专项项目指南 为有效应对近期发生的新型冠状病毒(2019-nCoV)感染肺炎疫情,增强新发突发传染病的防控能力,国家自然科学基金委员会现启动专项项目,支持所在依托单位具有相关生物安全研究条件的科研人员,紧密围绕新型冠状病毒(2019-nCoV)感染的病原学、流行病学、发病机制、疾病防治等相关重大科学问题,开展基础性、前瞻性的联合研究。本专项项目鼓励学科交叉,用新的科研范式理念系统解决关键科学问题,从而为新型冠状病毒感染及新发突发传染病防控提供理论及技术支撑。 一、拟资助研究方向 (一)新型冠状病毒的结构、功能、感染关键靶点及作用机制,以及不同冠状病毒差异性研究。 (二)新型冠状病毒溯源、变异与进化,以及新技术与“科赫假说”的再认识。 (三)新型冠状病毒感染的人群易感性及疾病流行规律。 (四)新型冠状病毒感染的发生、发展及转归机制,以及重症救治和医院感染防控的基础研究。 (五)冠状病毒应急疫苗和通用疫苗的基础研究。  二、资助计划 本专项项目资助期限为2年,申请书中的研究期限应填写为:2020年3月15日-2022年3月14日,直接费用资助强度约150万元/项。拟针对上述研究方向,择优资助约20项项目。 三、申请要求及注意事项 (一)申请条件 本专项项目申请人应当具备以下条件: 1.具有承担基础研究课题的经历; 2.具有高级专业技术职务(职称)。 在站博士后研究人员、正在攻读研究生学位以及无工作单位或者所在单位不是依托单位的人员不得作为申请人进行申请。 (二)限项申请规定 1.本专项项目不计入高级专业技术职务(职称)人员申请和承担总数2项的范围。 2.申请人和主要参与者只能同时申请和参与申请1项本专项项目。 3.申请人同年只能申请1项专项项目中的研究项目。 (三)申请注意事项 1.本专项项目要求坚持问题导向,强化需求牵引,注重交叉融合, 鼓励高等学校与研究院所等联合申请,提出具有创新思路的研究课题。 2.电子申请书提交时间为2020年2月3日--2月6日16时,纸质申请书请于2020年2月13日16时前以快递方式寄出(以邮戳日期为准),未按相关要求提交的申请项目将不予受理。合作研究单位数量不得超过2个。 3.申请人在填报申请书前,应当认真阅读本项目指南和《2020年度国家自然科学基金项目指南》中申请须知的相关内容,不符合项目指南相关要求的申请项目将不予资助。 4.申请人应根据本项目指南发布的拟资助研究方向确定研究内容。新型冠状病毒属于国家有关“高致病性病原微生物”界定范畴,申请人和依托单位必须严格遵守相关规定,在具备相应的安全条件下方可提出申请。申请人所在依托单位及合作研究单位均需提供项目研究不产生生物安全风险的证明材料,未按规定提供相关生物安全证明材料的项目申请将不予受理。涉及人的生物医学研究,必须严格遵守国家和有关部委关于“伦理和生物安全”的有关规定,申请人必须提供所在单位或上级主管单位伦理委员会的纸质审核证明,作为附件随申请书一并报送(电子申请书应附扫描件)。涉及人类遗传资源研究的,申请人和依托单位应严格遵守2019年7月1日起施行的《中华人民共和国人类遗传资源管理条例》的相关规定。 5.请申请人登录科学基金网络信息系统https://isisn.nsfc.gov.cn(没有系统账号的申请人请向依托单位基金管理联系人申请开户),按照撰写提纲及相关要求撰写申请书。申请代码1选择微生物学(C01)、医学病原生物与感染(H19)或者预防医学(H26)所属申请代码;“资助类别”选择“专项项目”;亚类说明选择“研究项目”;附注说明选择“科学部综合研究项目”。以上选择不准确或未选择的项目申请将不予受理。 6.申请人应根据《国家自然科学基金资助项目资金管理办法》的有关规定,以及《国家自然科学基金项目资金预算表编制说明》的具体要求,按照“目标相关性、政策相符性、经济合理性”的基本原则,认真编制《国家自然科学基金项目资金预算表》。 7.申请人完成申请书撰写后,在线提交电子申请书及附件材料,下载并打印最终PDF版本申请书,并保证纸质申请书与电子申请书内容一致。申请人应及时向依托单位提交签字后的纸质申请书原件以及要求提交的纸质材料原件等附件。 8.依托单位应对本单位申请人所提交申请材料的真实性和完整性进行审核,并在规定时间内将申请材料报送国家自然科学基金委员会。具体要求如下: (1)依托单位应在电子申请书截止时间前(2020年2月6日16时)通过科学基金网络信息系统逐项确认提交本单位电子申请书及附件材料,并于2020年2月13日16时(以邮戳日期为准)之前统一报送经单位签字盖章后的纸质申请书原件(一式一份)及要求报送的纸质附件材料。 (2)报送纸质申请材料时,还应提供由法定代表人签字、依托单位加盖公章的依托单位科研诚信承诺书(可在信息系统中下载)和申请项目清单,材料不完整不予接收。 (3)可将纸质申请材料直接送达或者邮寄至国家自然科学基金委员会项目材料接收组(地址:北京市海淀区双清路83号101房间,邮编100085,电话:010-62328591)。采用邮寄方式的,请在项目申请截止日期前(以发信邮戳日期为准)以快递方式邮寄,以免延误申请。 9.本专项项目咨询联系方式: (1)申请代码1为微生物学(C01)所属申请代码的 国家自然科学基金委员会生命科学部 联系人:杜全生 联系电话:010-62329221 电子邮件:duqs@nsfc.gov.cn (2)申请代码1为医学病原生物与感染(H19)所属申请代码的 国家自然科学基金委员会医学科学部 联系人:李恩中 联系电话:010-62329131 电子邮件:liez@nsfc.gov.cn (3)申请代码1为预防医学(H26)所属申请代码的 国家自然科学基金委员会医学科学部 联系人:闫章才 联系电话:010-62327195 电子邮件:yanzc@nsfc.gov.cn 国家自然科学基金委员会 2020年1月22日 论文:武汉冠状病毒和SARS病毒的类群“相邻,但不属于” 《中国科学:生命科学》:新型冠状病毒自然宿主或是蝙蝠 2020-01-21 14:24 2020年1月21日,中国科学院上海巴斯德研究所郝沛研究员、军事医学研究院国家应急防控药物工程技术研究中心钟武研究员和中科院分子植物卓越中心合成生物学重点实验室李轩研究员合作,在SCIENCE CHINA Life Sciences(《中国科学:生命科学》英文版),在线发表了题为“Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission”的论文。  该论文分析阐述了引起近期武汉地区肺炎疫情爆发的新型冠状病毒的进化来源,及与导致2002年广东“非典”疫情的SARS冠状病毒、“中东呼吸综合征”MERS冠状病毒的遗传进化关系,并通过对武汉的新型冠状病毒spike-蛋白的结构模拟计算,揭示了武汉新型冠状病毒spike-与人ACE2蛋白作用并介导传染人的分子作用通路。该成果评估了武汉新型冠状病毒的潜在人间传染力,为尽快确认传染源和传播途径、制定高效的防控策略提供了科学理论依据。 2019年12月以来,湖北省武汉市集中发生了不明原因肺炎疫情。流行病调查发现这些陆续出现的肺炎病例都与武汉市“华南海鲜市场”有关联。武汉市组织多学科专家会诊调查,利用实验检测等手段认定武汉地区肺炎疫情为病毒性肺炎。2020年1月8日,初步确认了一种新型冠状病毒为此次疫情的病原。 武汉地区的病毒性肺炎疫情爆发,与2002年广东爆发的“非典”疫情有很多相似的地方,都发生在冬季、初始发生都起源于人与动物市场交易的鲜活动物接触,而且都是由未知的冠状病毒病原导致。截至1月20日18时,我国境内累计报告新型冠状病毒感染的肺炎病例224例,其中确诊病例217例(武汉市198例,北京市5例,广东省14例);疑似病例7例(四川省2例,云南省1例,上海市2例,广西壮族自治区1例,山东省1例)。日本通报确诊病例1例,泰国通报确诊病例2例,韩国通报确诊病例1例。感染患者中有14个医护人员,该新型冠状病毒出现人传人并有扩散的趋势。 2020年1月10日,武汉新型冠状病毒的第一个基因组序列数据被公布,后来陆续有多个从患者身上分离的新型冠状病毒的基因组序列发布。这些新型冠状病毒基因组数据,为研究分析武汉新型冠状病毒的进化来源、致病病理机制提供了第一手资料。 为了解武汉新型冠状病毒与已知明确感染人的两种冠状病毒的关系,此论文的研究者通过对武汉新型冠状病毒基因组与2002年“非典”SARS冠状病毒、“中东呼吸综合征”MERS冠状病毒进行了全基因组比对,发现平均分别有~70%和~40%的序列相似性。其中不同冠状病毒与宿主细胞作用的关键spike基因(编码S-蛋白),有更大的差异性。  为了解析武汉新型冠状病毒的进化来源和可能的自然界宿主,研究者利用武汉新型冠状病毒和收集到大量冠状病毒数据进行了遗传进化分析。结果发现武汉新型冠状病毒属于Beta冠状病毒属(Betacoronavirus)。Betacoronavirus是蛋白包裹的单链正链RNA病毒,寄生和感染高等动物(包括人)。在进化树的位置上,与SARS(导致2002年“非典”)病毒和类SARS(SARS-like)病毒的类群相邻,但并不属于SARS和类SARS病毒类群。有意思的是它们进化上共同的外类群是一个寄生于果蝠的HKU9-1冠状病毒。所以武汉冠状病毒和SARS/类SARS冠状病毒的共同祖先是和HKU9-1类似的病毒。由于武汉冠状病毒的进化邻居和外类群都在各类蝙蝠中有发现,推测武汉冠状病毒的自然宿主也可能是蝙蝠。如同导致2002年“非典”的SARS冠状病毒一样,武汉冠状病毒在从蝙蝠到人的传染过程中很可能存在未知的中间宿主媒介。  由于武汉新型冠状病毒与2002年“非典”SARS病毒和“中东呼吸综合征”MERS病毒有很大的遗传距离,所以论文作者对武汉新型冠状病毒感染人的机制和通路进行了分析。SARS病毒的 S-蛋白和MERS病毒S-蛋白分别通过与人的ACE2蛋白或DPP4蛋白互作结合来感染人的呼吸道上皮细胞。作者首先比较了武汉冠状病毒与SARS和MERS病毒S-蛋白的宿主受体互作区(RBD区),发现在RBD区域中,武汉冠状病毒与SARS病毒比较相似,但与MERS病毒差异很大,所以排除了S-蛋白与DPP4互作感染人的可能。但是,武汉冠状病毒S-蛋白与人ACE2互作也存在很大困难-已经证明的SARS病毒S-蛋白与ACE2互作的5个关键氨基酸,在武汉冠状病毒中有4个发生了改变。  为了分析清楚这个问题,文章作者利用分子结构模拟的计算方法,对武汉冠状病毒S-蛋白和人ACE2蛋白进行了结构对接研究,获得了令人惊讶的结果。虽然武汉冠状病毒S-蛋白中与ACE2蛋白结合的5个关键氨基酸有4个发生了变化,但变化后的氨基酸,却整体性上非常完美的维持了SARS病毒S-蛋白与ACE2蛋白互作的原结构构象。尽管武汉新型冠状病毒的新结构与ACE2蛋白互作能力,由于丢失的少数氢键有所下降(相比SARS病毒S-蛋白与ACE2的作用有下降),但仍然达到很强的结合自由能(-50.6 kcal/mol)。这一结果说明武汉冠状病毒是通过S-蛋白与人ACE2互作的分子机制,来感染人的呼吸道上皮细胞。研究成果预测了武汉冠状病毒有很强的对人感染能力,为科学防控,制定防控策略和开发检测/干预技术手段奠定了科学理论基础。  这一研究成果,是在国家“重大新药创制”科技重大专项的支持下(应急医学药物新品种研发及其关键创新技术体系),由中国科学院上海巴斯德研究所、军事医学研究院国家应急防控药物工程技术研究中心和中科院分子植物卓越中心合成生物学重点实验室合作研究完成的。研究同时还获得了国家自然科学基金和中科院战略生物资源计划“生物资源衍生库”项目的支持。徐心恬、陈萍、王靖方为共同第一作者。 2020年1月21日,中国科学院上海巴斯德研究所郝沛研究员、军事医学研究院国家应急防控药物工程技术研究中心钟武研究员和中科院分子植物卓越中心合成生物学重点实验室李轩研究员合作,在SCIENCE CHINA Life Sciences(《中国科学:生命科学》英文版),在线发表了题为“Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission”的论文。 Dear Editor, The occurrence of concentrated pneumonia cases in Wuhan city, Hubei province of China was first reported on December 30, 2019 by the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission (WHO, 2020). The pneumonia cases were found to be linked to a large seafood and animal market in Wuhan, and measures for sanitation and disinfection were taken swiftly by the local government agency. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Chinese health authorities later determined and announced that a novel coronavirus (CoV), denoted as Wuhan CoV, had caused the pneumonia outbreak in Wuhan city (CDC, 2020). Scientists from multiple groups had obtained the virus samples from hospitalized patients (Normile, 2020). The isolated viruses were morphologically identical when observed under electron microscopy. One genome sequence (WH-Human_1) of the Wuhan CoV was first released on Jan 10, 2020, and subsequently five additional Wuhan CoV genome sequences were released (Zhang, 2020; Shu and McCauley, 2017) (Table S1 in Supporting Information). The current public health emergency partially resembles the emergence of the SARS outbreak in southern China in 2002. Both happened in winter with initial cases linked to exposure to live animals sold at animal markets, and both were caused by previously unknown coronaviruses. As of January 15, 2020, there were more than 40 laboratory-confirmed cases of the novel Wuhan CoV infection with one reported death. Although no obvious evidence of human-to-human transmission was reported, there were exported cases in Hong Kong China, Japan, and Thailand. Under the current public health emergency, it is imperative to understand the origin and native host(s) of the Wuhan CoV, and to evaluate the public health risk of this novel coronavirus for transmission cross species or between humans. To address these important issues related to this causative agent responsible for the outbreak in Wuhan, we initially compared the genome sequences of the Wuhan CoV to those known to infect humans, namely the SARS-CoV and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)-CoV (Cotten et al., 2013). The sequences of the six Wuhan CoV genomes were found to be almost identical (Figure S1A in Supporting Information). When compared to the genomes of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, the WH-human_1 genome that was used as representative of the Wuhan CoV, shared a better sequence homology toward the genomes of SARS-CoV than that of MERS-CoV (Figure S1B in Supporting Information). High sequence diversity between Wuhan-human_1 and SARS-CoV_Tor2 was found mainly in ORF1a and spike (S-protein) gene, whereas sequence homology was generally poor between Wuhan-human_1 and MERS-CoV. To understand the origin of the Wuhan CoV and its genetic relationship with other coronaviruses, we performed phylogenetic analysis on the collection of coronavirus sequences from various sources. The results showed the Wuhan CoVs were clustered together in the phylogenetic tree, which belong to the Betacoronavirus genera (Figure 1A). Betacoronavirus is enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus that infects wild animals, herds and humans, resulting in occasional outbreaks and more often infections without apparent symptoms. The Wuhan CoV cluster is situated with the groups of SARS/SARS-like coronaviruses, with bat coronavirus HKU9-1 as the immediate outgroup. Its inner joint neighbors are SARS or SARS-like coronaviruses, including the human-infecting ones (Figure 1A, marked with red star). Most of the inner joint neighbors and the outgroups were found in various bats as natural hosts, e.g., bat coronaviruses HKU9-1 and HKU3-1 in Rousettus bats and bat coronavirus HKU5-1 in Pipistrellus bats. Thus, bats being the native host of the Wuhan CoV would be the logical and convenient reasoning, though it remains likely there was intermediate host(s) in the transmission cascade from bats to humans. Based on the unique phylogenetic position of the Wuhan CoVs, it is likely that they share with the SARS/SARS-like coronaviruses, a common ancestor that resembles the bat coronavirus HKU9-1. However, frequent recombination events during their evolution may blur their path, evidenced by patches of high-homologous sequences between their genomes (Figure S1B in Supporting Information).  Click to view Download high-quality image Figure 1 Evolutionary analysis of the coronaviruses and modeling of the Wuhan CoV S-protein interacting with human ACE2. A, Phylogenetic tree of coronaviruses based on full-length genome sequences. The tree was constructed with the Maximum-likelihood method using RAxML with GTRGAMMA as the nucleotide substitution model and 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Only bootstraps ≥50% values are shown as filled circles. The host for each coronavirus is marked with corresponding silhouette. Known human-infecting betacoronaviruses are indicated with a red star. B, Amino acid sequence alignment of the RBD domain of coronavirus S-protein. Residues 442, 472, 479, 487, and 491 (numbered based on SARS-CoV S-protein sequence) are important residues for interaction with human ACE2 molecule. C, Structural modeling of the Wuhan CoV (WH-human_1 as representative) S-protein complexed with human ACE2 molecule. Middle panel: The model of the Wuhan CoV S-protein (brown ribbon) is superimposed with the structural template of the SARS CoV S-protein (light blue ribbon). The protein backbone structure of human ACE2 is represented in magenta ribbon. Left panel: The region is shown for hydrogen bonding interactions between Arg426 in S-protein and Gln325/Glu329 in ACE2. The relevant residues are presented in ball and stick representations. Right panel: The region is shown for hydrogen bonding interactions between Tyr436 in S-protein and Asp38/Gln42 in ACE2. Overall, there is considerable genetics distance between the Wuhan CoV and the human-infecting SARS-CoV, and even greater distance from MERS-CoV. This observation raised an important question whether the Wuhan CoV adopted the same mechanisms that SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV used for transmission cross species/humans, or involved a new, different mechanism for transmission. The S-protein of coronavirus is divided into two functional units, S1 and S2. S1 facilitates virus infection by binding to host receptors. It comprises two domains, the N-terminal domain and the C-terminal RBD domain that directly interacts with host receptors (Li, 2012). To investigate the Wuhan CoV and its host interaction, we looked into the RBD domain of its S-protein. The S-protein was known to usually have the most variable amino acid sequences compared to those of ORF1a and ORF1b from coronavirus (Hu et al., 2017). However, despite the overall low homology of the Wuhan CoV S-protein to that of SARS-CoV (Figure S1 in Supporting Information), the Wuhan CoV S-protein had several patches of sequences in the RBD domain having a high homology to that of SARS-CoV_Tor2 and HP03-GZ01 (Figure 1B). The residues at positions 442, 472, 479, 487, and 491 in SARS-CoV S-protein were reported to be at receptor complex interface and considered critical for cross-species and human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV (Li et al., 2005). Despite the patches of highly conserved regions in the RBD domain of the Wuhan CoV S-protein, four of the five critical residues are not preserved except Tyr491 (Figure 1B). Although the polarity and hydrophobicity of the replacing amino acids are similar, they raised serious questions about whether the Wuhan CoV would infect humans via binding of S-protein to ACE2, and how strong the interaction is for risk of human transmission. Note MERS-CoV S-protein displayed very little homology toward that of SARS-CoV in the RBD domain, due to the different binding target for its S-protein, the human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) (Raj et al., 2013). To answer the serious questions and assess the risk of human transmission of the Wuhan CoV, we performed structural modeling of its S-protein and evaluated its ability to interact with human ACE2 molecules. Based on the computer-guided homology modeling method, the structural model of the Wuhan CoV S-protein was constructed by Swiss-model using the crystal structure of SARS coronavirus S-protein (PDB accession: 6ACD) as a template (Schwede et al., 2003). Note the amino acid sequence identity between the Wuhan-CoV and SARS-CoV S-proteins is 76.47%. Then according to the crystal structure of SARS-CoV S-protein RBD domain complexed with its receptor ACE2 (PDB code: 2AJF), the 3-D complex structure of the Wuhan CoV S-protein binding to human ACE2 was modeled with structural superimposition and molecular rigid docking (Li et al., 2005) (Figure 1C). The computational model of the Wuhan CoV S-protein (using the WH-human_1 sequence as representative) showed a CαRMSD of 1.45 Å on the RBD domain compared to the SARS-CoV S-protein structure (Figure 1C). The binding free energies for the S-protein to human ACE2 binding complexes were calculated by MOE 2019 with amber ff14SB force field parameters (Maier et al., 2015). The binding free energy between the Wuhan CoV S-protein and human ACE2 was –50.6 kcal mol–1,whereas that between SARS-CoV S-protein and ACE2 was –78.6 kcal mol–1. A value of –10 kcal mol–1 is usually considered significant. Because of the loss of hydrogen bond interactions due to replacing Arg426 with Asn426 in the Wuhan CoV S-protein, the binding free energy for the Wuhan CoV S-protein increased by 28 kcal mol–1 when compared to the SARS-CoV S-protein binding. Although comparably weaker, the Wuhan CoV S-protein is regarded to have strong binding affinity to human ACE2. So to our surprise, despite replacing four out of five important interface amino acid residues, the Wuhan CoV S-protein was found to have a significant binding affinity to human ACE2. Looking more closely, the replacing residues at positions 442, 472, 479, and 487 in the Wuhan CoV S-protein did not alter the structural confirmation. The Wuhan CoV S-protein and SARS-CoV S-protein shared an almost identical 3-D structure in the RBD domain, thus maintaining similar van der Waals and electrostatic properties in the interaction interface. In summary, our analysis showed that the Wuhan CoV shared with the SARS/SARS-like coronaviruses a common ancestor that resembles the bat coronavirus HKU9-1. Our work points to the important discovery that the RBD domain of the Wuhan CoV S-protein supports strong interaction with human ACE2 molecules despite its sequence diversity with SARS-CoV S-protein. Thus the Wuhan CoV poses a significant public health risk for human transmission via the S-protein–ACE2 binding pathway. People also need to be reminded that risk and dynamic of cross-species or human-to-human transmission of coronaviruses are also affected by many other factors, like the host’s immune response, viral replication efficiency, or virus mutation rate. Acknowledgment This work was supported in part by grants from the National Science and Technology Major Projects for “Major New Drugs Innovation and Development” (directed by Dr. Song Li) (2018ZX09711003) of China, the National Key R&D Program (2018YFC0310600) of China, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771412), and Special Fund for strategic bio-resources from Chinese Academy of Sciences (ZSYS-014). We also acknowledge the National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention, China CDC; Wuhan Institute of Virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences; Institute of Pathogen Biology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College; and Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital for their efforts in research and collecting the data and genome sequencing sharing. In addition, we acknowledge GISAID (https://www.gisaid.org/) for facilitating open data sharing. Interest statement The author(s) declare that they have no conflict of interest. Supplement SUPPORTING INFORMATION Figure S1 Sequence similarity analysis among six Wuhan CoV genomes and between Wuhan CoV and the human-infecting coronaviruses, SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Table S1 Acknowledgement to the authors, originating and submitting laboratories of the sequences from GISAID The supporting information is available online at http://life.scichina.com and https://link.springer.com. The supporting materials are published as submitted, without typesetting or editing. The responsibility for scientific accuracy and content remains entirely with the authors. References [1]CDC. (2020). 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), Wuhan, China. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/novel-coronavirus-2019.html. Google Scholar [2]Cotten M., Watson S.J., Kellam P., Al-Rabeeah A.A., Makhdoom H.Q., Assiri A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Alhakeem R.F., Madani H., AlRabiah F.A., et al. Transmission and evolution of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Saudi Arabia: a descriptive genomic study. Lancet, 2013, 382: 1993-2002 CrossRef Google Scholar [3]Hu B., Zeng L.P., Yang X.L., Ge X.Y., Zhang W., Li B., Xie J.Z., Shen X.R., Zhang Y.Z., Wang N., et al. Discovery of a rich gene pool of bat SARS-related coronaviruses provides new insights into the origin of SARS coronavirus. PLoS Pathog, 2017, 13: e1006698 CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar [4]Li F.. Evidence for a common evolutionary origin of coronavirus spike protein receptor-binding subunits. J Virol, 2012, 86: 2856-2858 CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar [5]Li F., Li W., Farzan M., Harrison S.C.. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science, 2005, 309: 1864-1868 CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar [6]Maier J.A., Martinez C., Kasavajhala K., Wickstrom L., Hauser K.E., Simmerling C.. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J Chem Theor Comput, 2015, 11: 3696-3713 CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar [7]Normile, D. (2020). Mystery virus found in Wuhan resembles bat viruses but not SARS, Chinese scientist says. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/01/mystery-virus-found-wuhan-resembles-bat-viruses-not-sars-chinese-scientist-says. Google Scholar [8]Raj V.S., Mou H., Smits S.L., Dekkers D.H.W., Müller M.A., Dijkman R., Muth D., Demmers J.A.A., Zaki A., Fouchier R.A.M., et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature, 2013, 495: 251-254 CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar [9]Schwede T., Kopp J., Guex N., Peitsch M.C.. SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res, 2003, 31: 3381-3385 CrossRef PubMed Google Scholar [10]Shu, Y., and McCauley, J. (2017). GISAID: Global initiative on sharing all influenza data—from vision to reality. EuroSurveillance 22, PMCID: PMC5388101. Google Scholar [11]WHO. (2020). Pneumonia of unknown cause in China. https://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2020-pneumonia-of-unkown-cause-china/en/. Google Scholar [12]Zhang, Y.Z. (2020). Initial genome release of novel coronavirus. http://virological.org/t/initial-genome-release-of-novel-coronavirus/319?from=groupmessage. Google Scholar 转自“中国科学杂志”微信公众号1月21日消息。 中国科学杂志社是隶属于中国科学院和中国科学出版集团的学术期刊出版单位。

http://engine.scichina.com/publisher/scp/journal/SCLS?slug=abstracts  (原题为:《武汉新型冠状病毒的进化来源和传染人的分子作用通路》) https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/JC0fCMsZlgGPYy4L7xMpTg http://www.sohu.com/a/368214008_260616 |

一键同布到我集网·各家微博

一键同布到我集网·各家微博